The Audio Library of

Classic Southern Literature

1676 to 1923

Made possible by

Visit our Children's literature site

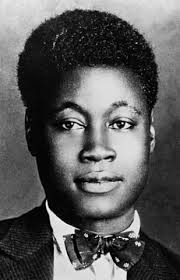

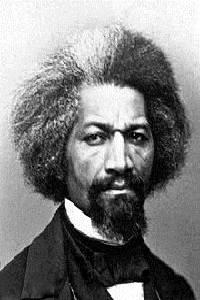

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Chapter 3

Written Text

Colonel Lloyd kept a large and finely cultivated garden, which afforded

almost constant employment for four men, besides the chief gardener,

(Mr. M'Durmond.) This garden was probably the greatest attraction of

the place. During the summer months, people came from far and near--from

Baltimore, Easton, and Annapolis--to see it. It abounded in fruits of

almost every description, from the hardy apple of the north to the

delicate orange of the south. This garden was not the least source of

trouble on the plantation. Its excellent fruit was quite a temptation to

the hungry swarms of boys, as well as the older slaves, belonging to the

colonel, few of whom had the virtue or the vice to resist it. Scarcely a

day passed, during the summer, but that some slave had to take the lash

for stealing fruit. The colonel had to resort to all kinds of stratagems

to keep his slaves out of the garden. The last and most successful one

was that of tarring his fence all around; after which, if a slave was

caught with any tar upon his person, it was deemed sufficient proof that

he had either been into the garden, or had tried to get in. In either

case, he was severely whipped by the chief gardener. This plan worked

well; the slaves became as fearful of tar as of the lash. They seemed to

realize the impossibility of touching _tar_ without being defiled.

The colonel also kept a splendid riding equipage. His stable and

carriage-house presented the appearance of some of our large city livery

establishments. His horses were of the finest form and noblest blood.

His carriage-house contained three splendid coaches, three or four gigs,

besides dearborns and barouches of the most fashionable style.

This establishment was under the care of two slaves--old Barney and young

Barney--father and son. To attend to this establishment was their sole

work. But it was by no means an easy employment; for in nothing was

Colonel Lloyd more particular than in the management of his horses. The

slightest inattention to these was unpardonable, and was visited upon

those, under whose care they were placed, with the severest punishment;

no excuse could shield them, if the colonel only suspected any want of

attention to his horses--a supposition which he frequently indulged, and

one which, of course, made the office of old and young Barney a very

trying one. They never knew when they were safe from punishment. They

were frequently whipped when least deserving, and escaped whipping when

most deserving it. Every thing depended upon the looks of the horses,

and the state of Colonel Lloyd's own mind when his horses were brought

to him for use. If a horse did not move fast enough, or hold his head

high enough, it was owing to some fault of his keepers. It was painful

to stand near the stable-door, and hear the various complaints against

the keepers when a horse was taken out for use. "This horse has not had

proper attention. He has not been sufficiently rubbed and curried, or

he has not been properly fed; his food was too wet or too dry; he got it

too soon or too late; he was too hot or too cold; he had too much hay,

and not enough of grain; or he had too much grain, and not enough

of hay; instead of old Barney's attending to the horse, he had very

improperly left it to his son." To all these complaints, no matter how

unjust, the slave must answer never a word. Colonel Lloyd could not

brook any contradiction from a slave. When he spoke, a slave must

stand, listen, and tremble; and such was literally the case. I have seen

Colonel Lloyd make old Barney, a man between fifty and sixty years of

age, uncover his bald head, kneel down upon the cold, damp ground, and

receive upon his naked and toil-worn shoulders more than thirty

lashes at the time. Colonel Lloyd had three sons--Edward, Murray, and

Daniel,--and three sons-in-law, Mr. Winder, Mr. Nicholson, and Mr.

Lowndes. All of these lived at the Great House Farm, and enjoyed the

luxury of whipping the servants when they pleased, from old Barney down

to William Wilkes, the coach-driver. I have seen Winder make one of the

house-servants stand off from him a suitable distance to be touched with

the end of his whip, and at every stroke raise great ridges upon his

back.

To describe the wealth of Colonel Lloyd would be almost equal

to describing the riches of Job. He kept from ten to fifteen

house-servants. He was said to own a thousand slaves, and I think this

estimate quite within the truth. Colonel Lloyd owned so many that he did

not know them when he saw them; nor did all the slaves of the out-farms

know him. It is reported of him, that, while riding along the road one

day, he met a colored man, and addressed him in the usual manner of

speaking to colored people on the public highways of the south: "Well,

boy, whom do you belong to?" "To Colonel Lloyd," replied the slave.

"Well, does the colonel treat you well?" "No, sir," was the ready reply.

"What, does he work you too hard?" "Yes, sir." "Well, don't he give you

enough to eat?" "Yes, sir, he gives me enough, such as it is."

The colonel, after ascertaining where the slave belonged, rode on;

the man also went on about his business, not dreaming that he had been

conversing with his master. He thought, said, and heard nothing more of

the matter, until two or three weeks afterwards. The poor man was then

informed by his overseer that, for having found fault with his master,

he was now to be sold to a Georgia trader. He was immediately chained

and handcuffed; and thus, without a moment's warning, he was snatched

away, and forever sundered, from his family and friends, by a hand more

unrelenting than death. This is the penalty of telling the truth, of

telling the simple truth, in answer to a series of plain questions.

It is partly in consequence of such facts, that slaves, when inquired

of as to their condition and the character of their masters, almost

universally say they are contented, and that their masters are kind.

The slaveholders have been known to send in spies among their slaves,

to ascertain their views and feelings in regard to their condition. The

frequency of this has had the effect to establish among the slaves the

maxim, that a still tongue makes a wise head. They suppress the truth

rather than take the consequences of telling it, and in so doing prove

themselves a part of the human family. If they have any thing to say of

their masters, it is generally in their masters' favor, especially when

speaking to an untried man. I have been frequently asked, when a

slave, if I had a kind master, and do not remember ever to have given a

negative answer; nor did I, in pursuing this course, consider myself as

uttering what was absolutely false; for I always measured the kindness

of my master by the standard of kindness set up among slaveholders

around us. Moreover, slaves are like other people, and imbibe prejudices

quite common to others. They think their own better than that of others.

Many, under the influence of this prejudice, think their own masters are

better than the masters of other slaves; and this, too, in some cases,

when the very reverse is true. Indeed, it is not uncommon for slaves

even to fall out and quarrel among themselves about the relative

goodness of their masters, each contending for the superior goodness of

his own over that of the others. At the very same time, they mutually

execrate their masters when viewed separately. It was so on our

plantation. When Colonel Lloyd's slaves met the slaves of Jacob Jepson,

they seldom parted without a quarrel about their masters; Colonel

Lloyd's slaves contending that he was the richest, and Mr. Jepson's

slaves that he was the smartest, and most of a man. Colonel Lloyd's

slaves would boast his ability to buy and sell Jacob Jepson. Mr.

Jepson's slaves would boast his ability to whip Colonel Lloyd. These

quarrels would almost always end in a fight between the parties, and

those that whipped were supposed to have gained the point at issue. They

seemed to think that the greatness of their masters was transferable to

themselves. It was considered as being bad enough to be a slave; but to

be a poor man's slave was deemed a disgrace indeed!